SUDDEN IMPACT CONCUSSION: Part 2 of 3.

How one head hit shattered the dreams of an NFL athlete.

George Visger’s memories are stored in little notebooks. He keeps hundreds of them filed away; daily logs of minor details that most take for granted.

The former defensive lineman for the San Francisco 49er suffered a concussion in 1980 on his first play. He has been dealing with the consequences since.

“I never used to regret playing football, but now I wish I never had. I was drafted by the Jets,

I played with the Niners for two years, I have a Super Bowl ring, but you know what? You can have it all. I used to say I’d do it all over again, but with what it’s done to my family? Hell no. I’ll never play again,” Visger said.

Despite the concussion, team doctors had Visger sniff more than 25 smelling salts and play through the pain. The result of his first play: an NFL career cut short and a devastating impact on Visger’s life.

“I was skinny, scrawny, slow and my nickname was Clang because when I ran, I was so skinny that my coaches would say they could hear my knees clang,” Visger said through laughter, recalling his days playing Pop Warner football for the West Stockton Bear Cubs. “But I had no doubt in my mind that I would be the greatest NFL player to ever live.”

His vision of NFL greatness ended after his career-ending hit.

Concussions are invisible injuries that leave lasting impacts in plain sight. Visger is one of scores of former NFL players who struggle daily with the chronic effects of a traumatic brain injury.

Playing professional football is associated with a significantly higher risk for permanent brain damage, according to a study conducted by Dr. Daniel Amen, an expert on brain imaging.

Brain damage, subsequent poor decisions, depression, sleep apnea, and obesity are commonly occurring symptoms of TBI, Amen said.

Experts agree that early detection and treatment of concussions is key.

If a concussion goes untreated upon incidence, treatment takes significantly longer, said David Kruse, an Orange-based sports medicine physician specializing in concussions who works with the Dons. “We have cases where athletes can’t return to full play for many months to a year, and it could get worse.”

Visger says that if he had been taken out of play after his first hit, his life would be very different.

“I may not have developed hydrocephalus or had nine brain surgeries since then. Do you know what this has done to my life? I have four different holes in my skull now,” said Visger, who has tubes draining spinal fluid from his skull into his abdomen 24 hours a day. Otherwise, “the back ventricles start filling up like water balloons and it starts crushing my brain from the inside out.”

The long-term effects of traumatic brain injury are not just confined to Visger.

“It’s been a nightmare for my family. They never know who’s coming home,” said 6-foot-5 inch, 230 pound Visger, who revealed that his family refers to him as the “Gentle Giant,” or “Maximum George” depending on his temper that night.

“Personality changes and emotional liability, which can include anger management issues, can be an effect of traumatic brain injury,” Kruse said.

“This totally floored me. I had no idea anyone in my family was suffering like this for years.

You don’t know. You think people are hypersensitive and I’m normal, but you know what? I’m not normal,” Visger said.

Early onset dementia is another long-term effect of TBI.

The general incidence of dementia between age 50 and 65 ranges from 0.3-to-2.2 percent, but in a study of 100 retired NFL players, 12 percent in this age-group had abnormal screen studies, according to Amen’s published paper.

Visger is not an exception. He was given his last rites at 23 years old during one of his first emergency brain surgeries, and faced his mortality again just two years ago.

“The doctor told me there was no cure for dementia. Told me to turn in my driver’s license, sign up for social security, and prepare my finances,” said Visger. “So what? I’m 52 and this is it? I don’t think so.”

Visger subsequently visited the Newport Beach based Amen Clinic where his signs of dementia have been reversed through specialized treatment.

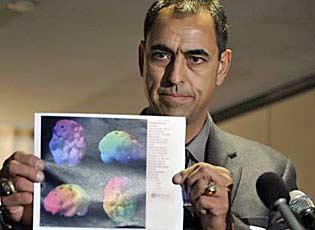

Using SPECT imaging scans of the brain, physicians are able to pinpoint parts of the brain that are effected by traumatic brain injuries and refer treatment from there, Amen said.

“We were able to demonstrate improvement in brain function and cognitive performance in retired players who sustained brain injuries often decades previously,” Amen states in a published paper, adding that about 70 percent of participants reported increases in memory after being treated.

Everyday, George tucks himself into a dark chamber about the size of a shuttle cockpit where pressurized oxygen is pumped into his body.

“When certain parts of the brain are damaged, sometimes cells go dormant, and hyperbarics gets oxygen to those parts of the brain tissue that aren’t receiving oxygen,” said David Martinez, a certified hyperbaric technologist, who recalled one patient in a vegetative state who recovered.

“After 80 treatments she was running and laughing,” Martinez said.

Visger has completed more than 200 hyperbaric sessions, and his microcognitive memory scores have improved about 15 percent.

“It’s an hour worth of treatment in the chamber, and I’m in there everyday. As long as I’m improving, I’ll keep doing it,” Visger said. “I shouldn’t be functioning the way I am. Someone is watching out for me. I think the Big Coach is on my side.”

Still, some football players at Santa Ana College do not take concussions seriously.

“I’m not really too concerned. I’m still playing, it’s not going to hold me back,” said Dons’ defensive back Chris Manassero, who suffered a concussion in Sept.

Visger warns these athletes of the dangers of their sport.

“You’re going to be in my shoes a lot sooner than you think. The old days of getting your bell rung and laughing about it, those days are over. It’s not a joke. It’s not a bell ringing. Why is it the most important organ in your body is a joke when you damage it? That’s a serious injury,” Visger said angrily. “We’re starting to get through to some [players], but some guys don’t want to hear it.”

Taking all things into account, Visger still retains a positive outlook on life.

“What my mom has always told me is that God gives crosses to those who can bear them.

What I’ve always done is turn negatives into positives. When something bad happens to me, I’ve always pictured that I have a fire in my belly burning and everything negative is a chunk of wood and instead of a negative thing knocking me down, I throw that wood in my fire and I just crank it up another notch,” Visger said.

NUMBER GAME

- 4 = Number of holes Visger has in his skull, draining fluid into his abdomen.

- 25 = Number of smelling salts Visger sniffed before heading back onto the field.

- 9 = Number of brain surgeries Visger has undergone.

RELATED STORY :

Head games: Sudden impact concussion

- The two-party system is failing us. - October 19, 2024

- Read our Fall 2023 Print: Vol. 100 No. 1 - October 23, 2023

- Santa Ana College Awarded State Department of Finance Grant - April 2, 2015