By: C. Harold Pierce

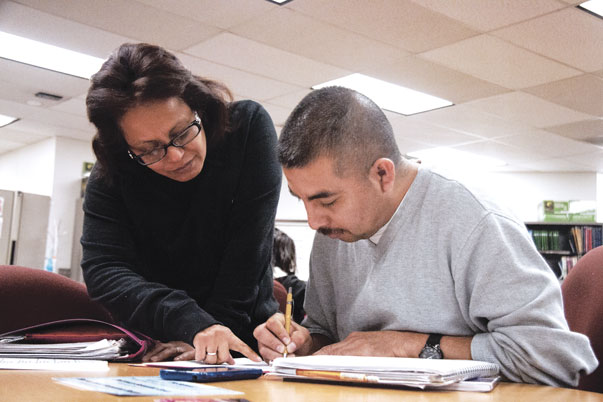

Three years ago, Gabriel Martinez, 31, lost control of his car on the freeway and crashed. Then came the sirens and paramedics. He slipped into a coma for nearly two months. When he woke up, he underwent two brain surgeries and as a result, lost most of his memory.

Since then, he has been working towards his high school diploma at Centennial Education Center, a state-funded school operated by Rancho Santiago Community College District that offers classes in English as a second language, general education degrees and career technical education at no cost.

“I started from zero. So far, I am what I am because of this school. Where will I go if this place shuts down? Nowhere. I’m 15 credits from getting my high school diploma. Without the credits, I don’t know what I’m going to do next,” Martinez said.

He is one of about 10,000 students who could be left without a school if the Santa Ana City Council does not extend the lease on the center’s 2.6-acre property at Centennial Park.

The council vote could potentially turn pivotal because a group of about 20 neighborhood association members want more recreational space at Centennial Park.

Starting in 1979, CEC, Godinez Fundamental High School and a police training facility have been constructed on the 47-acre space. Neighboring residents say they have slowly lost the park.

“We used to have big events here and everyone would come to this park because we had a lot of open space,” said Steve McGuigan, president of the Riverview West Neighborhood Association.

Neighborhood association leaders argue that ESL and adult education classes at CEC could be held anywhere in the city and should be scattered across Santa Ana, instead of at Centennial Park.

“Those are classes that before were being done in the Bristol Market Place in store fronts, proving that they could be done in an existing facility. They could be done in a shopping center across the street, in classrooms they rent from Godinez [High School] … or it could be done downtown where there is better need,” McGuigan said.

It’s a battle of two underdogs: a group of students struggling to keep their school, and a small circle of homeowners fighting for a park they once cherished.

About 48 percent of Santa Ana residents over the age of 25 do not have a high school diploma, and 20 percent of families do not have a household member above the age of 14 who can speak English, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“We’re the answer to that. That’s why we feel it’s absolutely critical that we’re allowed to retain our presence here,” Santa Ana College School of Continuing Education Interim Vice President James Kennedy said.

And some residents who do not attend association meetings feel the same way.

Windsor Village resident Grace Ramirez counts at least three friends on her street who attend classes at CEC.

“I went to school there to learn English and a little bit of computer. It’s not far from the people in this neighborhood, and lots of people from here go to school there,” Ramirez said.

Maggie Brown, a 40-year homeowner in Windsor Village and former neighborhood association member was part of the planning commission for CEC but did not know that Windsor Village Neighborhood Association was opposed to the center now.

“I feel that we don’t accurately represent the neighborhood association,” McGuigan said, noting that only about 20 people typically show up to meetings.

In order for CEC to keep its space, the city must fulfill a federal land swap requirement and find a comparable parcel of land for park space in Santa Ana. The crowded city is struggling to create more greenbelts, said Gerardo Mouet, executive director of the Parks, Recreation and Community Service Agency.

A vacant lot about half the size of CEC at the northeast corner of McFadden Avenue and Orange Avenue is being considered, but the appraisal value of the land fell short by about $500,000, Mouet said.

The city is scrambling to locate an additional chunk of land to make up the difference.

But community members oppose stringing pieces together, instead insisting on getting the park space closest to them.

The federal government, which deeded the land to the city with certain restrictions, has allowed an extension on the lease, but the city council has not yet added it to the agenda.

“We don’t really know for sure what’s going to happen. There’s no other facility like this that can support our services and students. You need a facility that has 30 classrooms and 400 parking spots. Where do you find that?” Kennedy said.

College officials favor a land swap, which is in line with Santa Ana’s attempt to increase park availability to an average of 1.48 acres per 1,000 residents. By contrast, Lake Forest has close to three acres per 1,000 residents.

But district officials are not about to budge.

While the initial investment for building construction was about $500,000 in 1976, the city does not charge RSCCD rent. Instead, the district pays for about 7 percent of maintenance expenses for common areas in the park. In 2012, it paid about $27,000, according to district records.

The district submitted plans to the Division of the State Architect in 2007 to construct a two-story building on the property at a cost of $7.5 million.

“We are so short of space, we are so crowded. My heart is really for everybody and education is No. 1, but this is a park, and we need more open space,” said Barbara Lamere, a 48-year resident and member of the WVNA.